Abstract

Synopsis

The antitumour agent paclitaxel has proved to be effective for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast or ovarian cancer, and limited data also indicate its clinical potential in patients with cervical or endometrial cancer. The regimen of paclitaxel administration has varied in clinical trials, the most common including a dosage of between 135 and 250 mg/m2 administered over an infusion period of 3 or 24 hours once every 3 weeks. Promising results have been achieved in phase I/II trials of a weekly regimen of paclitaxel (60 to 175 mg/m2).

The objective response rate in patients with metastatic breast cancer (either pretreated or chemotherapy- naive) is generally between 20 and 35% with paclitaxel monotherapy, which compares well with that of other current treatment options including the anthracycline doxorubicin. Combination therapy with paclitaxel plus doxorubicin appears superior to treatment with either agent alone in terms of objective response rate and median duration of response. However, whether combination therapy also provides a survival advantage remains unclear; recent results of a phase III study indicate that it does not. Paclitaxel is also a useful second- line option in some patients with anthracycline- resistant disease.

Combination therapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin has proved highly effective as first- line therapy for patients with advanced ovarian cancer, showing superior efficacy to cyclophosphamide/cisplatin in terms of progression- free survival time and median duration of survival. Combination therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin has also shown promising results. Paclitaxel monotherapy is a useful second- line option for patients with platinum- refractory metastatic ovarian cancer (objective response rates have ranged from 15 to 48%).

The major dose-limiting adverse events associated with paclitaxel include myelotoxicity and peripheral neuropathy. Paclitaxel has acceptable tolerability in most patients, although adverse events are common.

Conclusion. Paclitaxel generally appears to be as effective as other antineoplastic agents used in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, including doxorubicin. Importantly, it is a useful second- line option for some patients with anthracycline- resistant disease. Combination therapy with both paclitaxel and doxorubicin is a highly effective first- line option for metastatic breast cancer; however, recent results indicate no survival advantage versus monotherapy. Paclitaxel is a valuable agent for second- line treatment of patients with platinum- refractory metastatic ovarian cancer and, when combined with cisplatin or carboplatin, is recommended as first- line therapy for this disease.

Overview of Pharmacodynamic Properties

The ability of paclitaxel to bind to microtubules and inhibit the normal dynamic reorganisation of the microtubule network is thought to play an important role in inhibition of cell replication. Apoptosis has also been observed in cells exposed to paclitaxel.

Paclitaxel inhibits the growth of a wide variety of tumour cells including those of ovarian, breast, cervical and endometrial origin. This activity may be synergistically enhanced in vitro when paclitaxel is combined with other antineoplastic agents including cisplatin, doxorubicin and fluorouracil. However, the order in which cells are exposed to these agents appears to be an important determinant of synergism or antagonism. In addition, paclitaxel can enhance the sensitivity of many cell types to the effects of irradiation.

Paclitaxel-resistant tumours may have increased expression of the multidrug-resistance mdr-1 gene, alterations in α- or β-tubulin or altered expression of specific β-tubulin genes.

Other effects of paclitaxel include concentration-dependent suppression of human peripheral blood mononuclear and natural killer cell cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines, inhibition of microtubule-associated functions of neutrophils, and enhancement of stimulated release of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β and tumour necrosis factor-α. Paclitaxel has been associated with reversible neurological toxicity, most frequently resulting in numbness or paraesthesia, in some patients.

Overview of Pharmacokinetic Properties

Plasma concentrations of paclitaxel increase throughout intravenous infusion and decline thereafter. Plasma concentrations achieved at steady state with doses ≥ 135 mg/m2 are higher than concentrations shown in vitro to produce antimicrotubule effects.

The drug’s pharmacokinetic behaviour appears to be nonlinear after administration of doses of 135 or 175 mg/m2 by 3- or 24-hour infusion.

Initial plasma clearance is rapid, but it is followed by a more prolonged elimination period. Paclitaxel is 88 to 98% plasma protein bound and has a large volume of distribution.

The predominant route of elimination of paclitaxel is by hepatic metabolism and biliary clearance. The main metabolite is 6α-hydroxypaclitaxel.

Administration of paclitaxel prior to doxorubicin causes a significant increase in peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of the anthracycline and prolongation of both the distribution and elimination half-life of the latter drug. Cmax and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve for the anthracycline metabolite doxorubicinol were also significantly increased. No pharmacokinetic interaction was observed with the reverse schedule.

Clearance of paclitaxel may be reduced by prior administration of cisplatin, whereas carboplatin has no apparent effect. Fluconazole and ketoconazole inhibited the metabolism of paclitaxel in vitro.

Clinical Efficacy

Paclitaxel has proved to be an effective agent for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast or ovarian cancer and, although data are limited, also appears to have potential in patients with endometrial or cervical cancer. The most frequently used regimen in clinical trials has been a 3- or 24-hour infusion given once every 3 weeks. Dosages have ranged between 135 and 250 mg/m2. A weekly schedule of paclitaxel (60 to 175 mg/m2) has also shown promising results in recent phase I/II trials. Neutropenia is the most common dose-limiting toxicity.

Breast Cancer. In patients with advanced breast cancer, clinical response rates to paclitaxel monotherapy have ranged between 17 and 86%; most falling within the 20 to 35% range. The drug has shown efficacy in both chemotherapy-naive and previously treated patients (including some patients with anthracycline-resistant disease). The median duration of response is generally between 4 and 8 months and median survival between 9.5 and 22.2 months. Treatment efficacy appears to be dose related.

Comparisons with other antineoplastic regimens are limited; however, paclitaxel monotherapy appears to be at least as effective as standard CMFP (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil, prednisone) combination therapy (although overall survival tended to be longer with paclitaxel) and superior to mitomycin monotherapy. Recent results from phase III studies have shown variable results regarding the relative efficacy of paclitaxel versus doxorubicin. In one study, both drugs showed similar efficacy in terms of objective response rates, median time to treatment failure and median duration of survival, whereas in another, improvements in both the objective response rate and median progression-free survival were significantly in favour of doxorubicin.

Clinical response rates and the median duration of response are generally higher when patients are given combination therapy with paclitaxel and other antineoplastic agents than with paclitaxel alone. First-line combination therapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin produced objective response rates ranging from 69 to 94% in phase I/II studies, with complete responses in 8 to 41% of patients. The median duration of objective response was between 8 and 11 months and median time to disease progression was between 9 and 12 months. Results from a phase III study indicate that combination therapy with doxorubicin/paclitaxel is more effective than monotherapy with either agent in terms of clinical response rate and median time to treatment failure; however, no survival advantage was observed (median duration of survival 19 to 22 months for all treatment groups).

Objective response rates appear similar to those achieved with paclitaxel/doxorubicin when paclitaxel is combined with either epirubicin or cisplatin (although they are more variable). Combination therapy with cyclophosphamide and various high-dose regimens have also shown promising results.

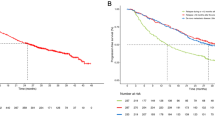

Ovarian Cancer. Paclitaxel monotherapy produced objective responses in 15 to 48% of patients with platinum-refractory advanced ovarian cancer in clinical trials with ≥44 participants. The median duration of response ranged from 4.9 to 9.2 months, median duration of progression-free survival from 14 weeks to 12 months and overall survival time from 8.1 to 15.6 months. As with breast cancer, response rates tended to be dose related.

Combination therapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin or carboplatin achieved response rates generally between 70 and 79% when used to treat patients with no prior chemotherapy experience.

When used as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic ovarian cancer, combination therapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin has proved to be superior to cyclophosphamide/cisplatin in terms of survival benefit. In a phase III study, the median progression-free survival time was 18 versus 13 months and median duration of survival was 38 versus 24 months (p < 0.001). The objective response rate was 73 versus 60% (p = 0.01).

Pharmacoeconomic analyses tended to favour combination therapy with cisplatin and paclitaxel with regard to long term survival benefit. Although first-line treatment costs were higher with this regimen than with cisplatin/cyclophosphamide, when the survival benefit was incorporated into the analyses, there was a moderate increase in incremental costs for cisplatin/paclitaxel which compared well with that of other life-prolonging therapies.

Tolerability

The most common adverse events in patients treated with paclitaxel include neutropenia, anaemia, peripheral neuropathy, myalgia/arthralgia, mucositis and alopecia. Treatment discontinuation because of severe events is rarely necessary [16 of 458 patients (4%) withdrew in one study].

Myelotoxicity is often dose limiting, but neutropenia usually resolves within 3 to 10 days. Furthermore, myelotoxicity may be reduced by administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. The incidence of myelotoxicity appears higher with a 24- versus a 3-hour infusion, and with a dose of 175 mg/m2 versus 135 mg/m2. Whereas paclitaxel showed similar haematological tolerability to standard CMFP therapy, its tolerability relative to that of doxorubicin was unclear. However, paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 was far better tolerated than doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 in a phase III study (grade 4 neutropenia 40 vs 85% and neutropenic fever 7 vs 20%). Haematological toxicity may be greater with paclitaxel/carboplatin combination therapy than with paclitaxel/cisplatin; however, this requires confirmation. The tolerability of paclitaxel/cisplatin relative to cisplatin/cyclophosphamide has yet to be clarified.

The administration schedule used may affect the tolerability of combination therapy. Haematological toxicity was greater when paclitaxel preceded doxorubicin (although this may not be the case with a shorter infusion time) or cyclophosphamide or when cisplatin preceded paclitaxel compared with the respective reverse schedules.

Peripheral neuropathy is a common nonhaematological toxicity which can be dose limiting in paclitaxel recipients. Its severity and incidence appear to be dose and schedule related, cumulative and occur earlier in the course of therapy when higher doses are administered. Patients with pre-existing neuropathy or other risk factors for neuropathy tend to be at greater risk. The incidence of peripheral neuropathy may be increased (compared with paclitaxel monotherapy) when paclitaxel is administered after, or in combination with, cisplatin. Myalgia or arthralgia also develop 2 to 3 days after paclitaxel administration in some patients (59% of 458 patients in one study) and appear to be dose related. However, most events are mild to moderate.

Cardiovascular events occur in a small number of patients treated with paclitaxel. However, the majority of events, including transient asymptomatic bradycardia and hypotension, are rarely considered to be clinically relevant. It remains unclear whether the incidence of cardiac toxicity is increased (versus doxorubicin) when paclitaxel is combined with doxorubicin. Although some phase II studies have shown a significant reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction in patients treated with the combination, and the development of congestive heart failure in some patients, results from a phase III study indicate that the incidence of cardiac toxicity is similar in patients treated with doxorubicin alone or in combination with paclitaxel. Paclitaxel plus epirubicin appears well tolerated with respect to possible cardiac events, although data are limited.

Other adverse events include alopecia (in most patients), mucositis and nausea and vomiting (common but rarely severe), and, less frequently, taste impairment, diarrhoea, anorexia, sore throat, stomatitis, fatigue, fever, oedema, hypotension, hypomagnesaemia, dyspnoea, headache, facial flushing, phlebitis, transient hepatocellular dysfunction and hypersensitivity reactions.

Dosage and Administration

Paclitaxel 135 or 175 mg/m2 administered intravenously over a 3-hour infusion period once every 3 weeks is recommended for the treatment of patients with ovarian cancer, and 175 mg/m2 by 3-hour intravenous infusion once every 3 weeks is recommended for patients with breast cancer. Subsequent courses of paclitaxel should be administered only when neutrophil and platelet counts have recovered to an adequate level, and the dosage should be reduced by 20% if patients develop severe neutropenia or severe peripheral neuropathy. The drug may be given either as first-line therapy or to patients who have received prior chemotherapy.

First-line combination therapy with paclitaxel preceded by doxorubicin appears to be more effective than paclitaxel monotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer, and first-line combination therapy with cisplatin or carboplatin after paclitaxel appears more effective than paclitaxel monotherapy in patients with metastatic ovarian cancer.

Premedication with oral dexamethasone, intravenous diphenhydramine (or clemastine) and cimetidine or ranitidine is recommended to reduce the risk of hypersensitivity reactions to paclitaxel. Continuous cardiac monitoring is not necessary during paclitaxel therapy, except in patients with serious pre-existing conduction abnormalities.

Although few data are available concerning the use of paclitaxel in patients with liver impairment, lower dosages of the drug should be administered to these patients.

As paclitaxel is poorly soluble in water, it is formulated in a vehicle of 50% polyoxyethylated castor oil and 50% alcohol (ethanol).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Spencer CM, Faulds D. Paclitaxel: a review of it pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in the treatment of cancer. Drugs 1994; 48(5): 794–847

Belotti D, Nicoletti I, Vergani V, et al. Paclitaxel (Taxol), a microtubule affecting drug, inhibits tumour induced angiogenesis [abstract no. 397]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1996; 37: 57

Oktaba AMC, Hunter W, Arsenault AL. Taxol: a potent inhibitor of normal and tumour-induced angiogenesis [abstract no. 2702]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1995; 36: 454

Klauber N, Parangi S, Flynn E, et al. Inhibition of angiogeneis and breast cancer in mice by the microtubule inhibitors 2-methoxyestradiol and taxol. Cancer Res 1997 Jan 1; 57: 81–6

Chi CW, Chang Y-F, Li L, et al. Taxol induced cytotoxicity in a human hepatoma cell line Hep3B [abstract no. 2759]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1994; 35: 462

Saunders DE, Lawrence WD, Christensen C, et al. Taxol-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells [abstract no. 1888]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1994; 35: 317

Liu Y, Bhalla K, Hill C, et al. Evidence for involvement of tyrosine phosphorylation in taxol-induced apoptosis in a human ovarian tumor cell line. Biochem Pharmacol 1994 Sep 15; 48: 1265–72

Ibrado AM, Ponnathpur V, Reed J, et al. Protein kinase C and tyrosine kinase activities affect taxol induced apoptosis in human leukemic cells [abstract no. 1866]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1994; 35: 314

Milas L, Hunter NR, Kurdoglu B, et al. Kinetics of mitotic arrest and apoptosis in murine mammary and ovarian tumors treated with taxol. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1995 Feb; 35: 297–303

Belotti D, Rieppi M, Nicoletti MI, et al. Paclitaxel (Taxol) inhibits motility of paclitaxel-resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res 1996 Oct; 2: 1725–30

Klaassen U, Harstrick A, Schleucher N, et al. Activity- and schedule-dependent interactions of paclitaxel, etoposide and hydroperoxy-ifosfamide in cisplatin-sensitive and -refractory human ovarian carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer 1996 Jul; 74: 224–8

Vanhoefer U, Harstrick A, Wilke H, et al. Schedule-dependent antagonism of paclitaxel and cisplatin in human gastric and ovarian carcinoma cell lines in vitro. Eur J Cancer A 1995; 31A(1): 92–7

Kano Y, Akutsu M, Tsunoda S, et al. In vitro schedule-dependent interaction between paclitaxel and cisplatin in human carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1996 Apr; 37: 525–30

Jekunen AP, Christen RD, Shalinsky DR, et al. Synergistic interaction between cisplatin and taxol in human ovarian carcinoma cells in vitro. Br J Cancer 1994 Feb; 69: 299–306

Untch M, Sevin B-U, Perras JP, et al. Evaluation of paclitaxel (taxol), cisplatin, and the combination paclitaxel-cisplatin in ovarian cancer in vitro with the ATP cell viability assay. Gynecol Oncol 1994 Apr; 53: 44–9

Crown J, Fennelly D, Schneider J, et al. Escalating dose Taxol + high-dose (HD) cyclophosphamide(C)/G-CSF as induction and to mobilize peripheral blood progenitors for use as rescue following multiple courses of HD carboplatin/C: a phase I trial in ovarian cancer patients [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1994 Mar; 13: 262

Kano Y, Akutsu M, Tsunoda S, et al. Schedule-dependent interaction between paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil in human carcinoma cell lines in vitro. Br J Cancer 1996 Sep; 74: 704–10

Martin DS, Stolfi RL, Colofiore JR, et al. Marked enhancement in vivo of paclitaxel’s (taxol’s) tumor-regressing activity by ATP-depleting modulation. Anticancer Drugs 1996 Aug; 7: 655–9

Berkova N, Page M. Addition of hTNFα potentiates cytotoxicity of taxol in human ovarian cancer lines. Anticancer Res 1995 May-Jun; 15: 863–6

Seong J, Milross CG, Hunter NR, et al. Potentiation of antitumor efficacy of paclitaxel by recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α. Anticancer Drugs 1997 Jan; 8: 80–7

Kurbacher CM, Wagner U, Kolster B, et al. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) improves the antineoplastic activity of doxorubicin, cisplatin, and paclitaxel in human breast carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Lett 1996 Jun 5; 103: 183–9

Erlich E, Potkul R, McCall A, et al. Paclitaxel is only a weak radiosensitizer of human cervical carcinoma cell lines [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Jan; 60: 117

Rodriguez M, Sevin B-U, Perras J, et al. Paclitaxel: a radiation sensitizer of human cervical cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol 1995 May; 57: 165–9

Suzuki M, Saga Y, Sekiguchi I, et al. Sensitization of human uterine cervical cancer cells to radiation using paclitaxel. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 1996 Jun; 57: 430–7

Jaakkola M, Rantanen V, Grénman S, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma cell lines are sensitive to paclitaxel in vitro. Anticancer Res 1997 Mar-Apr; 17: 939–44

Kavallaris M, Kuo DY-S, Burkhart CA, et al. Taxol-resistant epithelial ovarian tumors are associated with altered expression of specific beta-tubulin isotypes. J Clin Invest 1997 Sep 1; 100: 1282–93

Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC. Paclitaxel (Taxol). N Engl J Med 1995 Apr 13; 332: 1004–14

Gianni L, Kearns CM, Gianni A, et al. Nonlinear pharmacokinetics and metabolism of paclitaxel and its pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships in humans. J Clin Oncol 1995 Jan; 13: 180–90

Huizing MT, van Warmerdam LJC, Rosing H, et al. Limited sampling strategies for investigating paclitaxel pharmacokinetics in patients receiving 175 mg/m2 as a 3-hour infusion. Clin Drug Invest 1995 Jun; 9: 344–53

Rubens RD. Improving treatment for advanced breast cancer. Cancer Surv 1993; 18: 199–208

Wiernik PH, Schwartz EL, Strauman JJ, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of taxol. Cancer Res 1987 May 1; 47: 2486–93

Rowinsky EK, Burke PJ, Karp JE, et al. Phase I and pharmacodynamic study of taxol in refractory acute leukaemias. Cancer Res 1989; 49: 4640–7

Wiernik PH, Schwartz E, Einzig A, et al. Phase I trial of taxol given as a 24-hour infusion every 21 days: responses observed in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1987; 5: 1232–9

Wright M, Monsarrat B, Alvinerie P, et al. Hepatic metabolism and biliary excretion of taxol. Abstract from the Second National Cancer Institute Workshop on Taxol and Taxus; 1992 Sep 23–24; Alexandria, 1992

Walle T, Bhalla KN, Walle UK, et al. Taxol disposition in humans after tritium-labelled drug [abstract no. 404]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1994; 13: 152

Huizing MT, Vermorken JB, Rosing H, et al. Pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and three major metabolites in patients with advanced breast carcinoma refractory to anthracycline therapy treated with a 3-hour paclitaxel infusion: a European Cancer Centre (ECC) trial. Ann Oncol 1995 Sep; 6: 699–704

Gianni L, Viganò L, Locatelli A, et al. Human pharmacokinetic characterization and in vitro study of the interaction between doxorubicin and paclitaxel in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997 May; 15: 1906–15

Holmes FA, Madden T, Newman RA, et al. Sequence-dependent alteration of doxorubicin pharmacokinetics by paclitaxel in a phase I study of paclitaxel and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996 Oct; 14: 2713–21

Rowinsky EK, Gilbert MR, McGuire WP, et al. Sequences of taxol and cisplatin: a phase I and pharmacologic study. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 1692–703

Siddiqui N, Boddy AV, Thomas HD, et al. A clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel for epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 1997; 75(2): 287–94

Calvert AH, Boddy A, Bailey NP, et al. Carboplatin in combination with paclitaxel in advanced ovarian cancer: dose determination and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions. Semin Oncol 1995 Oct; 22Suppl. 12: 91–8

Calvert A. The use of pharmacokinetics to improve the treatment of ovarian cancer: combination paclitaxel (Taxol)-carboplatin. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1997; 7Suppl. 1: 14–7

Greco FA, Hainsworth JD. One-hour paclitaxel infusion schedules: a phase I/II comparative trial. Semin Oncol 1995 Jun; 22 (3 Suppl. 6): 118–23

Klaassen U, Wilke H, Strumberg D, et al. Phase I study with a weekly 1 h infusion of paclitaxel in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic breast and ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer A 1996 Mar; 32A: 547–9

Eisenhauer EA, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, Swenerton KD, et al. European-Canadian randomized trial of paclitaxel in relapsed ovarian cancer: high-dose versus low-dose and long versus short infusion. J Clin Oncol 1994 Dec; 12: 2654–66

Hortobagyi GN, Holmes FA. Single-agent paclitaxel for the treatment of breast cancer: an overview. Semin Oncol 1996 Feb; 23Suppl. 1: 4–9

Fennelly D, Aghajanian C, Shapiro F, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of paclitaxel administered weekly in patients with relapsed ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997 Jan; 15: 187–92

Rischin D, Webster LK, Millward MJ, et al. Cremophor pharmacokinetics in patients receiving 3-, 6-, and 24-hour infusions of paclitaxel. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996 Sep 18; 88: 1297–301

Seidman AD, Hochhauser D, Gollub M, et al. Ninety-six-hour paclitaxel infusion after progression during short taxane exposure: a phase II pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996 Jun; 14: 1877–84

Chang AY, Boros L, Garrow G, et al. Paclitaxel by 3-hour infusion followed by 96-hour infusion on failure in patients with refractory malignant disease. Semin Oncol 1995 Jun; 22Suppl. 6: 124–7

Gelmon KA. Biweekly paclitaxel in the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1995 Oct; 22Suppl. 12: 117–22

Seidman AD, Murphy B, Hudis C, et al. Activity of Taxol (T) by weekly 1 hour infusion in patients (pts) with metastatic breast cancer (MBC): a phase II and pharmacologic study [abstract no. 517]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 148a

Breier S, Lebedinsky C, Pelayes L, et al. Phase I/II weekly paclitaxel (P) 80 mg/m in pretreated patients (pts) with breast (BC) and ovarian cancer (OC) [abstract no. 568]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 163. N

McCaffrey JA, Seidman AD, Tong W, et al. A phase II and pharmacologic study of Taxol by weekly one-hour infusion in the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer [abstract]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1996; 41(3): 234

Sikov WM, Akerley W, Cummings F, et al. Weekly high-dose paclitaxel in locally advanced (LABC)and metastatic (MBC) breast cancer [abstract no. 412]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997; 46: 95

Chang AY, Boros L, Asbury R, et al. Dose-escalation study of weekly 1-hour paclitaxel administration in patients with refractory cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 17: 69–71

Francis P, Rowinsky E, Schneider J, et al. Phase I feasibility and pharmacologic study of weekly intraperitoneal paclitaxel: a Gynecologic Oncology Group pilot study. J Clin Oncol 1995 Dec; 13: 2961–7

Abrams JS, Vena DA, Baltz J, et al. Paclitaxel activity in heavily pretreated breast cancer: a National Cancer Institute Treatment Referral Center trial. J Clin Oncol 1995 Aug; 13: 2056–65

Bonneterre J, Tubiana-Hulin M, Chollet P, et al. Taxol (paclitaxel) 225 mg/m2 by 3-hour infusion without G-CSF as a first-line therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [abstract no. 179]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996; 15: 128

Davidson NG. Single-agent paclitaxel as first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer: the British experience. Semin Oncol 1996 Oct; 23Suppl. 11: 6–10

Fountzilas G, Athanassiades A, Giannakakis T, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel in advanced breast cancer resistant to anthracyclines. Eur J Cancer A 1996 Jan; 32A: 47–51

Gianni L, Munzone E, Capri G, et al. Paclitaxel in metastatic cancer: a trial of two doses by a 3-hour infusion in patients with disease recurrence after prior therapy with anthracyclines. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995 Aug 2; 87: 1169–75

Mamounas E, Brown A, Fisher B, et al. 3-Hour (hr) high-dose taxol (T) infusion in advanced breast cancer (ABC): an NSABP phase II study [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1995 Mar; 14: 127

Seidman AD, Tiersten A, Hudis C, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel by 3-hour infusion as initial and salvage chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1995 Oct; 13: 2575–81

Swain SM, Honig SF, Tefft MC, et al. A phase II trial of paclitaxel (Taxol Rm) as first line treatment in advanced breast cancer. Invest New Drugs 1995; 13(3): 217–22

Awada A, Paridaens R, Bruning P, et al. Doxorubicin or Taxol as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer (MBC): results of an EORTC-IDBBC/ECSG randomised trial with crossover [abstract no. 2]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997; 46: 23

Bishop JF, Dewar J, Tattersall MHN, et al. Taxol (paclitaxel) injection alone is equivalent to CMFP combination chemotherapy as frontline treatment in metastatic breast cancer [abstract no. 538]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 153a

Dieras V, Marty M, Tubiana N, et al. Phase II randomized study of paclitaxel versus mitomycin in advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1995 Aug; 22Suppl. 8: 33–9

Nabholtz J-M, Gelmon K, Bontenbal M, et al. Multicenter, randomized comparative study of two doses of paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996 Jun; 14: 1858–67

Sledge GW, Neuberg D, Ingle J, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin (A) vs paclitaxel (T) vs doxorubicin + paclitaxel (A+T) as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer: an intergroup trial [abstract no. 2 and slides]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 1a

Reed E, Bitton R, Sarosy G, et al. Paclitaxel dose intensity. J Infus Chemother 1996 Spring; 6: 59–63

Bishop JF, Dewar J, Toner GC, et al. Paclitaxel as first-line treatment for metastatic breast cancer. Oncology 1997 Apr; 11Suppl. 3: 19–23

Amadori D, Frassineti GL, Zoli W, et al. A phase I/II study of sequential doxorubicin and paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1996 Oct; 23Suppl. 11: 16–22

Dombernowsky P, Gehl J, Boesgaard M, et al. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel, a highly active combination in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1996 Oct; 23Suppl. 11: 23–7

Dombernowsky P, Boesgaard M, Andersen E, et al. Doxorubicin plus paclitaxel in advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 17: 15–8

Fisherman JS, Cowan KH, Noone M, et al. Phase I/II study of 72-hour infusional paclitaxel and doxorubicin with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996 Mar; 14: 774–82

Gianni L, Munzone E, Capri G, et al. Paclitaxel by 3-hour infusion in combination with bolus doxorubicin in women with untreated metastatic breast cancer: high antitumor efficacy and cardiac effects in a dose-finding and sequence-finding study. J Clin Oncol 1995 Nov; 13: 2688–99

Klein JL, Dansey RD, Karanes C, et al. Induction chemotherapy with doxorubicin and paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer [abstract no. 405]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997; 46: 94

Martin M, Lluch A, Ojeda B, et al. Paclitaxel plus doxorubicin in metastatic breast cancer: preliminary analysis of cardiotoxicity. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 17: 26–30

Schwartsmann G, Mans DR, Menke CH, et al. A phase II study of doxorubicin/paclitaxel plus G-CSF for metastatic breast cancer. Oncology 1997 Apr; 11Suppl. 3: 24–9

Carmichael J, Jones A, Hutchinson T, et al. A phase II trial of epirubicin plus paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 17: 44–7

Catimel G, Spielmann M, Dieras V, et al. Phase I studies of combined paclitaxel/epirubicin and paclitaxel/epirubicin/cyclophosphamide in patients with metastatic breast cancer: the French experience. Semin Oncol 1997 Feb; 24Suppl. 3: 8–12

Conte PF, Michelotti A, Baldini E, et al. A dose-finding study of epirubicin in combination with paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1996 Oct; 23Suppl. 11: 28–31

Lück H-J, Du Bois A, Thomssen C, et al. Paclitaxel and epirubicin as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncology 1997 Apr; 11Suppl. 3: 34–7

Ezzat A, Raja MA, Berry J, et al. A phase II trial of circadiantimed paclitaxel and cisplatin therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 1997 Jul; 8: 663–7

Gelmon KA, O’Reilly SE, Tolcher AW, et al. Phase I/II trial of biweekly paclitaxel and cisplatin in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996 Apr; 14: 1185–91

Sparano JA, Neuberg D, Glick JH, et al. Phase II trial of biweekly paclitaxel and cisplatin in advanced breast carcinoma: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1997 May; 15: 1880–4

Wasserheit C, Frazein A, Oratz R, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel and cisplatin in women with advanced breast cancer: an active regimen with limiting neurotoxicity. J Clin Oncol 1996 Jul; 14: 1993–9

Kennedy MJ, Zahurak ML, Donehower RC, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of sequences of paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide supported by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in women with previously treated metastatic breast cancer [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 1996 Mar; 14: 783–91

Pagani O, Sessa C, Martinelli G, et al. Dose-finding study of paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide in advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol 1997 Jul; 8: 655–61

Tolcher AW, Cowan KH, Noone MH, et al. Phase I study of paclitaxel in combination with cyclophosphamide and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in metastatic breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1996 Jan; 14: 95–102

Holmes FA. Update: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience with paclitaxel in the management of breast carcinoma. Semin Oncol 1995 Aug; 22Suppl. 8: 9–15

Sledge GW, Neuberg D, Ingle J, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin (A) vs paclitaxel (T) vs doxorubicin + paclitaxel (A + T) as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer (MBC): an intergroup trial [abstract no.2]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 1a

Fountzilas G, Athanassiadis A, Kalogera-Fountzila A, et al. Paclitaxel by 3-h infusion and carboplatin in anthracyclineresistant advanced breast cancer. A phase II study conducted by the Helenic Cooperative Oncology Group. Eur J Cancer 1997; 33: 1893–5

Chang AY, Boros L, Garrow GC, et al. Ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide, and paclitaxel chemotherapy: a dose-escalation study. Semin Oncol 1996 Jun; 23 (3 Suppl. 6): 74–7

Cagnoni PJ, Shpall EJ, Bearman SI, et al. Paclitaxel-containing high-dose chemotherapy: the University of Colorado experience. Semin Oncol 1996 Dec; 23Suppl. 15: 43–8

Hudis C. Sequential dose-dense adjuvant therapy with doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and cyclophosphamide. Oncology 1997 Apr; 11Suppl. 3: 15–8

Rahman Z, Champlin R, Rondon G, et al. Phase I/II study of dose-intense doxorubicin/paclitaxel/cyclophosphamide with peripheral blood progenitor cells and cytokine support in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 17: 77–80

Hainsworth JD, Jones SE, Mennel RG, et al. Paclitaxel with mitoxantrone, fluorouracil, and high-dose leucovorin in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 1996 May; 14: 1611–6

Klaassen U, Harstrick A, Wilke H, et al. Preclinical and clinical study results of the combination of paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1996 Feb; 23Suppl. 1: 44–7

Klaassen U, Wilke H, Müller C, et al. Infusional 5-FU, folinic acid, paclitaxel, and cisplatin for metastatic breast cancer. Oncology 1997 Apr; 11Suppl. 3: 38–40

Nicholson B, Paul D, Shyr Y,et al. Paclitaxel/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin in metastatic breast cancer: a Vanderbilt Cancer Center phase II trial. Semin Oncol 1997 Aug; 24Suppl. 11: 20–3

Paul DM, Garrett AM, Meshad M, et al. Paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil in metastatic breast cancer: the US experience. Semin Oncol 1996 Feb; 23Suppl. 1: 48–52

Thigpen JT, Blessing JA, Vance RB, et al. Chemotherapy in ovarian carcinoma: Present role and future prospects. Semin Oncol 1989; 16(4) Suppl. 6: 58–65

Ozols RF. Ovarian cancer part II: treatment. Curr Probl Cancer 1992; 16: 61–126

Aravantinos G, Skarlos DV, Kosmidis P, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel in platinum pretreated ovarian cancer. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study. Eur J Cancer A 1997 Jan; 33: 160–3

du Bois A, Luck HJ, Buser K, et al. Extended phase II study of paclitaxel as a 3-h infusion in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with plantinum. Eur J Cancer 1997 Mar; 33: 379–84

Gore ME, Levy V, Rustin G, et al. Paclitaxel (Taxol) in relapsed and refractory ovarian cancer: the UK and Eire experience. Br J Cancer 1995 Oct; 72: 1016–9

Kohn EC, Sarosy G, Bicher A, et al. Dose-intense taxol: high response rate in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994 Jan 5; 86: 18–24

Phillips KA, Friedlander M, Olver I, et al. Australasian multicentre phase II study of paclitaxel (Taxol) in relapsed ovarian cancer. Aust N Z J Med 1995 Aug; 25: 337–43

Rowinsky EK, Mackey MK, Goodman SN. Meta analysis of paclitaxel (P) dose-response and dose-intensity (DI) in recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer (OC) [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996 Mar; 15: 284

Seewaldt VL, Greer BE, Cain JM, et al. Paclitaxel (Taxol) treatment for refractory ovarian cancer: phase II clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994 Jun; 170: 1666–71

Trimble EL, Adams JD, Vena D, et al. Paclitaxel for platinum-refractory ovarian cancer: results from the first 1,000 patients registered to National Cancer Institute Treatment Referral Center 9103. J Clin Oncol 1993 Dec; 11: 2405–10

Uziely B, Groshen S, Jeffers S, et al. Paclitaxel (Taxol) in heavily pretreated ovarian cancer: antitumor activity and complications. Ann Oncol 1994 Nov; 5: 827–33

Markman M. Paclitaxel in the management of ovarian cancer: what we know and what we have yet to learn. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1996 Feb; 122: 71–3

McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 1996 Jan 4; 334: 1–6

Goldberg JM, Piver MS, Hempling RE, et al. Paclitaxel and cisplatin combination chemotherapy in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Dec; 63: 312–7

Hoskins WJ, McGuire WP, Brady MF, et al. Combination paclitaxel (Taxol) — cisplatin vs cyclophosphamide-cisplatin as primary therapy in patients with suboptimally debulked advanced ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1997; 7Suppl.1: 9–13

Reed E, Sarosy G, Kohn E, et al. A phase I study of paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide in recurrent adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Jun; 61: 349–53

Kohn EC, Sarosy GA, Davis P, et al. A phase I/II study of dose-intense paclitaxel with cisplatin and cyclophosphamide as initial therapy of poor-prognosis advanced-stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Aug; 62: 181–91

Kurbacher CM, Bruckner HW, Cree IA, et al. Mitoxantrone combined with paclitaxel as salvage therapy for platinum-refractory ovarian cancer: laboratory study and clinical pilot trial. Clin Cancer Res 1997 Sep; 3: 1527–33

O’Reilly S, Fleming GF, Baker SD, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacologic trial of sequences of paclitaxel and topotecan in previously treated ovarian epithelial malignancies: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1997 Jan; 15: 177–86

Dimopoulos MA, Papadimitriou C, Gennatas C, et al. Ifosfamide and paclitaxel salvage chemotherapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 1997 Feb; 8: 195–7

Miglietta L, Amoroso D, Bruzzone M, et al. Paclitaxel plus ifosfamide in advanced ovarian cancer: a multicenter phase II study. Oncology 1997 Mar-Apr; 54: 102–7

Adams M, Kirby IJ, Rocker I, et al. A comparison of the toxicity and efficacy of cisplatin and carboplatin in advanced ovarian carcinoma. Acta Oncol 1989; 28: 57–60

Rozencweig M, Martin A, Betlangady M, et al. Randomised trials of cisplatin and carboplatin in advanced ovarian cancer. In: Bunn PA, Canetta R, Ozols RF, et al., editors. Carboplatin: current perspectives and future directions. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990: 175–92.

Bolis G, Scarfone G, Zanaboni F, et al. A phase I-II trial of fixed-dose carboplatin and escalating paclitaxel in advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer A 1997 Apr; 33: 592–5

Bookman MA, McGuire WP, Kilpatrick D, et al. Carboplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian carcinoma: a phase I study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1996 Jun; 14: 1895–902

du Bois A, Lück H-J, Bauknecht T, et al. Phase I/II study of the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 1997; 8: 355–61

Huizing MT, van Warmerdam LJC, Rosing H, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of the combination paclitaxel and car-boplatin as first-line chemotherapy in stage III and IV ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997 May; 15: 1953–64

Ozols RF. Gynecologic oncology group trials in ovarian carcinoma. Semin Oncol 1997 Feb; 24Suppl. 2: 10–2

Neijt JP, Hansen M, Hansen SW, et al. Randomised phase III study in previously untreated epithelial ovarian cancer FIGO stage IIB, IIC, III, IV, comparing paclitaxel-cisplatin and paclitaxel-carboplatin [abstract no. 1259]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 352a

du Bois A, Luck H-J, Meier W, et al. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel as first-line chemotherapy in previously untreated advanced ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 11: S11–28

McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Comparison of combination therapy with paclitaxel Taxol and cisplatin versus cyclophosphamide and cisplatin in patients with suboptimal stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1996; 6Suppl. 1: 2–8

McGuire W, Neugut AI, Arikian A, et al. Analysis of the cost-effectiveness of paclitaxel as alternative combination therapy for advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 640–5

Ortega A, Dranitsaris G, Sturgeon J, et al. Cost-utility analysis of paclitaxel in combination with cisplatin for patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1997 Sep; 66: 454–63

Covens A, Roche K, Macdonald M. Is paclitaxel cisplatin cost-effective as first-line therapy in advanced ovarian cancer? [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Jan; 60: 140

Messori A, Trippoli S, Becagli P. Pharmacoeconomic profile of paclitaxel as a first-line treatment for patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: a lifetime cost-effectiveness analysis. Cancer 1996 Dec 1; 78: 2366–73

Elit LM, Gafni A, Levine MN. Economic and policy implications of adopting paclitaxel as first-line therapy for advanced ovarian cancer: an Ontario perspective. J Clin Oncol 1997 Feb; 15: 632–9

Ball HG, Blessing JA, Lentz SS, et al. A phase II trial of paclitaxel in patients with advanced or recurrent adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Aug; 62: 278–81

Lissoni A, Zanetta G, Losa G, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel as salvage treatment in advanced endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol 1996 Oct; 7: 861–3

Woo HL, Swenerton KD, Hoskins PJ. Taxol is active in platinum-resistant endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 1996 Jun; 19: 290–1

Kudelka AP, Winn R, Edwards CL, et al. An update of a phase II study of paclitaxel in advanced or recurrent squamous cell cancer of the cervix. Anticancer Drugs 1997 Aug; 8: 657–61

McGuire WP, Blessing JA, Moore D. Paclitaxel has moderate activity in squamous cervix cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1996 Mar; 14: 792–5

Costa MA, Rocha JCC, Araújo CM, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel and cisplatin as primary medical treatment in locally advanced cervical cancer: preliminary results [abstract]. Ann Oncol 1996; 7Suppl. 5: 71

Taxol (paclitaxel) for injection concentrate. In advanced ovarian cancer after failure of first-line or subsequent chemotherapy. Princeton; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, 1993

Bristol-Myers Squibb. Taxol (paclitaxel) injection prescribing information. Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997

McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Comparison of combination therapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin versus cyclophosphamide and cisplatin in patients with suboptimal stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Semin Oncol 1997 Feb; 24 (1 Suppl. 2): S13–16

Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, Stuart G, et al. Is cisplatin-paclitaxel (P-T) the standard in first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer (Ov Ca)? The EORTC-GCCG NOCOVA NCI-C and Scottish intergroup experience [abstract no. 1258]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 352a

Postma TJ, Vermorken JB, Liefting AJ, et al. Paclitaxel-induced neuropathy. Ann Oncol 1995 May; 6: 489–94

Cavaletti G, Bogliun G, Marzorati L, et al. Peripheral neurotoxicity of taxol in patients previously treated with cisplatin. Cancer 1995 Mar 1; 75: 1141–50

Gordon AN, Stringer CA, Matthews CM, et al. Phase I dose escalation of paclitaxel in patients with advanced ovarian cancer receiving cisplatin: rapid development of neurotoxicity is dose-limiting. J Clin Oncol 1997 May; 15: 1965–73

Connelly E, Markman M, Kennedy A, et al. Paclitaxel delivered as a 3-hr infusion with cisplatin in patients with gynecologic cancers: unexpected incidence of neurotoxicity. Gynecol Oncol 1996 Aug; 62: 166–8

Hortobagyi GN, Willey J, Rahman Z, et al. Prospective assessment of cardiac toxicity during a randomized phase II trial of doxorubicin and paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1997; 24Suppl. 17: S17–65 - S17-68

Merouani A, Davidson SA, Schrier RW. Increased nephrotoxicity of combination taxol and cisplatin chemotherapy in gynecologic cancers as compared to cisplatin alone. Am J Nephrol 1997; 17: 53–8

Sledge JGW, Antman KM. Progress in chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1992; 19: 317–32

Rubens RD. Key issues in the treatment of advanced breast cancer: expectations and outcomes. Pharmacoeconomics 1996; 9Suppl. 2: 1–7

Mourisden HT. Systemic therapy of advanced breast cancer. Drugs 1992; 44Suppl. 4: 17–28

Forgeson G. Guidelines for the use of expensive medicines [letter]. N Z Med J 1995 Mar 22; 108: 111

Borowitz M, Hutton J, Rothman M. A cost-utility study of docetaxel (D) and paclitaxel (P) in the treatment of recurrent metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in the US [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1995 Mar; 14: 106

Brown R, Hutton J. Cost-utility comparisons of chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer: results of an international study [abstract]. Annual Meeting of the International Society of Technology Assessment and Health Care; 1997 May 25–28; Barcelona, Spain

Peters BG, Dunphy FR, Hill JJ, et al. Docetaxel and paclitaxel for the treatment of anthracycline-resistant metastatic breast cancer: a pharmacoeconomic model. Pharmacol Ther 1997 Nov: 543–52

Partridge EE, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on ovarian cancer treatment in United States hospitals. Cancer 1996 Nov 15; 78: 2236–46

Lorigan PC, Crosby T, Coleman RE. Current drug treatment guidelines for epithelial ovarian cancer. Drugs 1996 Apr; 51: 571–84

Markman M, Rothman R, Hakes T, et al. Second line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with platinum. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 389–93

Ozols RF. Treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer: increasing options — ‘recurrent’ results. J Clin Oncol 1997 Jun; 15: 2177–80

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiseman, L.R., Spencer, C.M. Paclitaxel. Drugs Aging 12, 305–334 (1998). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-199812040-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-199812040-00005